The Well-Known American Humanity

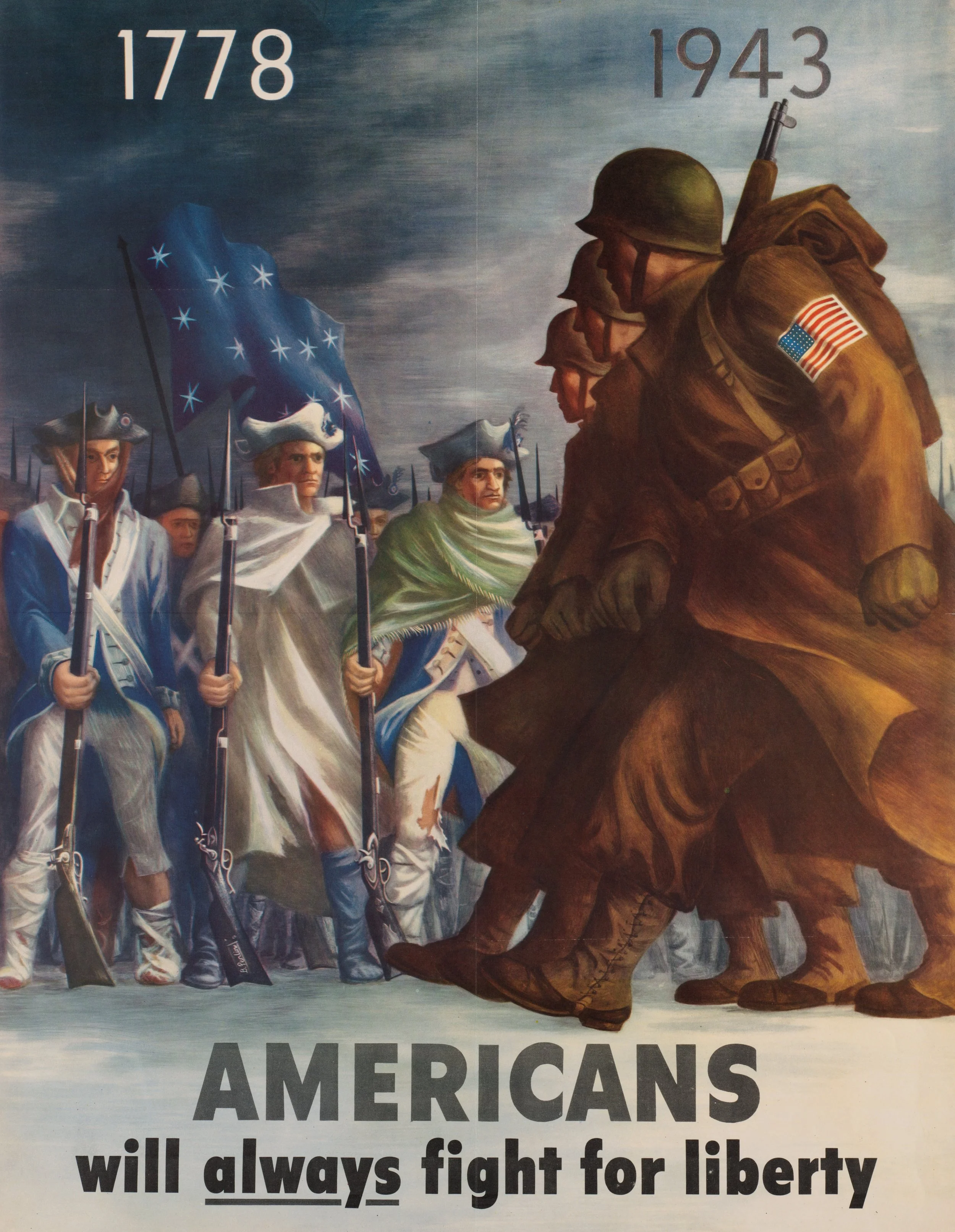

November 11th the world over has been set aside as a day to honor the memory of the men and women who have served their nations. In the United States, we call it Veteran’s Day. In other nations, it’s known as Remembrance Day.

In the USA, the spirit of solders has always been synonymous with promoting and preserving liberty all over the world and protecting those who strive to be free from tyrannical oppression.

Here at Whiskers on Kittens that service commands our full respect.

The spirit of the American soldier is a sacred thing. The warp and weft of it weaves the fabric which creates the garment of freedom. That spirit embodies many attributes, but there are three specific ones which I believe are intrinsic and seen time and again in our fighting men and women. These attributes are almost synonymous with the American soldier. They are the well-known American humanity.

Let me set the stage:

December 1944. Bastogne, Belgium. The highway hub of the densely forested Ardennes region.

The 101st Airbourne have been in the thick of war for months now. They were the tip of the spear, sending pathfinders behind the Normandy beaches in June 1944. They pressed on and cleared the way for the Allied Forces through France and the Netherlands. After months of intensive fighting, the 101st has been re-outfitting in Reims. They had been awarded much earned leave to go to Paris. Some of the men leap at that chance. Others merely take the opportunity to catch up on their sleep.

However, aside from a few prescient officers, such as General Patton himself, no one in the Allied camp foresaw the German Operation Watch on the Rhine, an offensive attack through the Ardennes region with the objective to get troops across the Meuse River and secure Antwerp again for the Reich. Because the Allied Forces are unprepared, the Germans are able to take significant group, and what was once looking like a clear cut military victory for the Allies is now in serious jeopardy.

Operation Watch on the Rhine second objective is to divide the Allied Forces, a powerful reenactment of the old adage divide and conquer. Unfortunately for the Allies, this seems to be working out well for the Germans. They are effectively spearheading an attack that the America newspapers are calling the Bulge.

The terrain is difficult. The weather is not helping.

Since the 101st wasn’t planning on going into heavy battle in such ungainly terrain, they are ill prepared. Certainly, they have the ammo and K-rations. What they don’t have is the winter gear. No coats, wool socks, long underwear. These battle-hardened warriors know this next mission will not be easy. Yet, they do not complain. They simply move forward.

Since Operation Watch on the Rhine has started, thousands of American troops have been killed or captured. It hasn’t even been a week.

As they head to Bastogne, the 101st encounter retreating troops, all but broken by the warfare they have seen. Negative prognostications are given, such as “You’ll all be killed”. Undaunted, they press on.

Arriving in Bastogne on the 19th of December, General Tony McAuliffe of the 101st relieves Major General Troy Middleton of the VIII Army who has preformed admirably under the harsh conditions thrown at him. After a turn over of detailed information, Middleton warns McAuliffe somewhat jocularly not to let himself get surrounded. Then he heads several miles outside of Bastogne.

The Germans seem to think they can just push through the American defenses, take Bastogne, and press on to the Meuse River. After two days of intensive fighting, they think better of this plan. Instead, they decide to lay siege to Bastogne, surround the American troops there, and use that stranglehold to defeat them.

The 101st Airbourne is under siege. They have been fighting heavily for four days. Now the Germans have cut off the last road open out of Bastogne toward Neuchateau. They are surrounded. More and more German troops are amassing. The 101st can see them along the southern outskirts of Bastogne.

Yet, in spite of little sleep, continuous fighting, and dwindling supplies- medical, food, and ammunition- General McAuliffe maintains that stoic optimism associated with the 101st. His attitude mirrors the words of one of the medics in the field hospital:

“They have us surrounded. Poor bastards.”

Tenacious

tenacious: Not readily relinquishing a position, principle, or course of action; determined.

December 22nd, 1944, Late Morning

Four Germans- a major, a captain, and two enlisted men- present themselves. They carry a white bedsheet in lieu of a truce flag. They declare themselves parlementaires, an archaic French term for a diplomatic go-between, and declare they wish to see the American commander.

After blindfolding them and marching them around camp in a haphazard manner so that the Germans are not able to grasp their surroundings or get their bearings, the parlementaires are brought to General McAuliffe.

They present him with a letter written in both German and English. The original is somewhat florid and wordy, but the essence is that the Germans are offering the Americans terms of surrender.

Upon first hearing the letters contents, McAuliffe is famed to have remarked, “Aw, nuts!”

Regardless of the fact that they were surrounded, the 101st didn’t see their circumstance as hopeless. They are ready to give the Nazis ‘one hell of a fight.’ But they also know that Bastogne was of strategic military importance to win out against the advancing Germans.

Furthermore, the terms of surrender are accompanied with a significant threat.

“If this proposal should be rejected, one German artillery corps and six heavy A.A. battalions are ready to annihilate the U.S.A. troops in and near Bastogne. The order for firing will be given immediately after this two hours’ term… All serious civilian losses caused by this artillery fire would not correspond with the well known American humanity.”

Sobering terms. Surrender or die. You will not be taken as prisoners. You will be killed. Period.

How does McAuliffe respond?

His answer is not flippant. He knows that how he answers is of supreme importance. History will record his words. They must reflect the fact that the Americans will hold firm. They will not relinquish their position.

The response is hastily typed:

To the German Commander,

‘NUTS!’

The American Commander

McAuliffe hands the written respond to Colonel Harper and orders him to see it delivered. Reading it quickly, Harper nods and says, “I will deliver it myself. It will be a lot of fun.”

The Germans are escorted out of camp. When they read McAuliffe’s reply, they lose the gist of it in translation. They appeal to Harper for clarity. Harper obliges.

“If you don’t understand what ‘Nuts’ means, in plain English it is the same as ‘Go to hell.’ And I will tell you something else—if you continue to attack we will kill every goddam German that tries to break into this city.”

The line has been drawn in the sand. No one in the 101st Airbourne will leave Bastogne alive unless they hold the town until they are relieved. Rumor has it that Patton’s Third Army is pushing hell for leather through the weather and the terrain to do just that.

So, the 101st will hold the line till then or die trying.

Valiant

valiant: possessing or showing courage or determination.

December 26th, 1944

A few miles outside Bastogne. Atop a hill. Lt. Col. ‘Abe’ Abrams of the 37th Tank Battalion of the 4th Armored Division in Patton’s Third Army leans out the turret hatch of his Sherman tank, Thunderbolt VII, watching the airdrops of supplies into besieged Bastogne. The cargo planes are slow moving and easy targets for the Germans. Abrams has lost count of the number of planes shot down, their fire engulfed wreckage riddling the landscape around Bastogne.

Abrams’ orders are to capture the city of Sibret, northwest of Bastogne. But he does not proceed. He can’t. He’s only a few miles from Bastogne. He knows the 101st need to have relief and have it soon. And he believes he and his 37th Tank Battalion are just the ones to provide that relief.

He radios in a request. Rather than take Sibret, he wants to move the 37th toward Bastogne in the most direct way possible- through the hamlets of Assenois and Clochimont. The two hamlets are controlled by the Germans. He proposes to focus the full force of his artillery on Assenois and Clochimont, destroy that German control, and the move on to come to the aid of the 101st.

When Patton receives the request, he orders the attack.

Progress is slow. Sherman tanks move at about 30 miles per hour at top speed. Though they come under heavy attack, they do not lose a single tank. When a shell knocks a pole across the road, it’s Abrams himself with several other men who brave the barrage of fire to move it.

When they reach Assenois, the battle only intensifies. Things get hairy when the American artillery observer is hit before he can radio the order to cease fire. So, as Abrams’ 37th takes Assenois, they have to endure friendly fire. Chaos ensues until a spotter plane pilot sees what’s going on and is able to relay the message to the Americans to stop firing.

Onward the 37th moves. What they encounter next are mines buried along the road by the Germans. None of the tanks are hit. But, when a halftrack is and explodes, movement comes to halt again.

One brave soldier, Captain William Dwight gets out of his tank, walks ahead, and clears the road of the mines one by one. He is fully exposed to enemy fire the entire time.

The battle rages long into the night. And while slow, progress is still being made. By the afternoon of the next day, after nearly twenty-four hours of continuous battle, the Sherman tanks roll into Bastogne. They are not met with cheers. Rather, from the foxholes, they see guns trained on them.

First Lieutenant Charles Boggess opens the hatch of his tank, Cobra King, and shouts out in English,

“Come here! Come on out! This is the Fourth Armored.”

Still no move is made. No gun is lowered. Finally, a lone officer, appears and introduces himself.

“I’m Lieutenant Webster, of the 326th Engineers, 101st Airbourne Division. Glad to see you.”

The sentiment is echoed some time later by McAuliffe when he greets Abrams.

“Gee, am I mighty glad to see you.”

After a week long siege, Bastogne has been relieved and victory achieved.

Altruistic

altruistic: showing a disinterested and selfless concern for the well-being of others; unselfish.

December 1944

Not all victories are on the battlefields. Nor is every act of bravery.

The Battle of the Bulge lasted from December 16th, 1944 to January 25th, 1945. During that time, there was great loss of life on both sides. There were also many prisoners of war taken as well.

One of those prisoners of war captured during the battle in December is Knoxville native Master Sgt. Roddie Edmonds. Captured, crammed into a boxcar, and then forced marched through harsh winter conditions, Edmonds finds himself in Ziegenhain, Germany in the POW camp, Stalag IXA.

Edmonds is the highest ranking officer of the 1,292 American soldiers brought to the camp. When one of the prison guards approaches him with instructions that every American soldiers who is Jewish needed to present himself the next day, Edmonds knows what they means. Either those soldiers will be sent to concentration camps or they will be shot outright.

Master Sgt. Roddie Edmonds gives a single order to his men.

The next day dawns. No one can be sure whether the sun is shining or not. Drab gray is the color of everything in the POW camp. The bleakness of the prisoners seems to permeate the very atmosphere.

The prison guards calls for all the Jews to stand up and identify themselves. The soldiers take a moment to take stock of each other. Then they all fall into formation, standing at attention. All 1,292 American soldiers.

The prison guards are flabbergasted. There is no way they can call be Jewish. When they relay their disbelief to Edmonds, he stands more erect and declares,

“We are all Jews.”

This clear act of defiance enrages the German commander present. He unsheathes his gun and presses it into the Master Sgt. Roddie Edmonds forehead, his finger poised on the trigger.

Edmonds does not relent. Nor do any of his men. Rather, he gives the German commander a lecture.

“According the Geneva Convention, we only have to give our name, rank, and serial number. If you shoot me, you’ll have to shoot all of us, and after the war, you will be tried for war crimes, and you will pay.”

The reply does not assuage the German commander, but it does serve as a reminder. He sheaths his pistol and storms off, leaving Edmonds and his 1,292 men standing in the yard.

The responsibility for so many men is gargantuan. Shouldering it in a POW camp is unfathomable. Yet, Edmonds must have remember Benjamin Franklin’s words:

“We must hang together or we will all hang separately.”

The number cannot be positively confirmed, but it is believes that Edmonds order, and the obedience of the 1,292 men who followed it, saved 200 American POWs that day.

Acts of tenacity, valiancy, and altruism from our brave men and women are countless. The three I chronicled today are merely a single drop in an infinite bucket. Yet, each story is an apt distillation of the attributes intrinsic to the spirit of a great soldier.

The one part I find myself continually drawn to in all these stories is the concluding line in the terms of surrender the Germans handed General McAuliffe.

“All serious civilian losses caused by this artillery fire would not correspond with the well known American humanity.”

The well-known American humanity. Even our arch enemies understand our character. To an American G.I., each life is important. Preserving the innocent a top priority. Defending liberty from tyranny a continual quest. Our enemies may see this as weakness. Yet, it is our greatest strength.

Americans prize the individual. We do not view the world through a collective prism, but honor the individuality of every citizen. The framework of our nation was built with this principle in mind, and it will only continue to function properly so long as this principle is honored. This is the spirit of our soldiers. This is why they fight.

And though I know personally many servicemen and women who are currently living with regret and shame concerning the decisions surrounding the ignominious withdrawal from Afghanistan and the United States’ current perception in the world given the horrors witnessed and continuing there to this day, their service, their sacrifice is of the same caliber as the men I’ve written about today.

“The noble fight is always noble - odds and outcome matter to the mortal, not the immortal. In times like this, we must remember - and remind every veteran - that their commitment transcends the field of battle.”

You are seen. Your bravery is known. Your courage and sacrifice are remembered. You have taken up the baton from the generations before in this continual, noble fight for liberty. And to you we are humbly and abidingly grateful.